We’re so excited to share that FactSet’s “Not Just the Facts” campaign has earned three major wins at the 2025 ANA B2 Awards, which celebrate the very best in business-to-business marketing.

Developed with our amazing client FactSet, the campaign challenged the conventions of boring B2B financial marketing by spotlighting a common frustration: financial professionals need data, but facts without context are useless. With a smart, tongue-in-cheek approach, “Not Just the Facts” positioned FactSet as the antidote—offering insights that are as meaningful as they are actionable.

These awards reflect the power of blending creative bravery with strategic clarity, and what’s possible when a brand is willing to break away from the usual B2B playbook. Congratulations to everyone involved in bringing this vision to life, and thank you to ANA and the jury for this honor.

This year, VSAers are embarking on an ambitious journey to redesign logos, websites, apps, packaging and more. It’s our contribution to businesses, brands and society by exploring potential solutions to the many types of expressions and experiences in the world we think have the potential of being better. We have not been commissioned for these solutions, but rather it’s our passion for great creativity that motivates us.

.gif)

In some instances, we’ll be considering what exists today. At other times, we’ll consider the opportunity for something yet to be solved, but we see it as critical for the future.

%20(1).gif)

Visit design4better.co to see the ever-evolving sketchpad for ambitious concepts that push design and organizations forward. From bold ideas to new interactions, we create with curiosity and purpose.

See the ads that have people commenting “Am I being trolled?”, “Someone call the exorcist” and “Wait, was this on purpose?” (Yes. Yes, it was.)

We’re super excited to share the “Keep It Real” campaign, created in partnership with computer security company McAfee. “Keep It Real” raises awareness about the rise of AI-driven scams while also working to shift the culture of shame that surrounds being scammed.

The campaign blends thumb-stopping digital ads that use AI to spark conversation about what’s real and fake online with Scam Stories—a movement that empowers scam survivors to speak out, reduce stigma and help others stay safe. Together, these elements create a powerful, human-centered effort to inform, connect and protect.

“By using AI in our ads with intention, we’re recreating the same confusion and doubt people experience when faced with a scam, creating a need to look twice,” said Stephanie Fried, Chief Marketing Officer at McAfee. “And in parallel, Scam Stories gives voice and power to the real people behind those moments. Holistically, this campaign helps shift the narrative from shame to understanding, and reminds people that anyone can be fooled. Seeing is no longer believing—we cannot rely on our instincts to help us tell real from fake. We need powerful tools to keep us safe and give us peace of mind.”

The creative ad campaign was developed in partnership with VSA Partners and launched alongside McAfee’s Scam Detector, a new feature that uses AI to automatically spot scams across text, email and video. While the ads lean into the surreal, the message is serious: With AI blurring the lines between real and fake, people need help telling the difference.

The campaign’s digital ads—set against a variety of backgdrops, including travel, weight loss and tolls—were designed to make people pause and think. One of the first spots to gain traction shows a woman lounging on a beach when her head suddenly rotates a full 360 degrees. Online reactions were immediate. Some assumed it was a post-production error. Others thought it was a deepfake gone wrong. And while a few viewers realized it was intentional, many were left wondering whether the moment was accidental or planned. That uncertainty was part of the point.

“The ads are clearly artificial—but that’s intentional,” said Anne-Marie Rosser, CEO of VSA Partners. “We wanted them to feel just real enough to make people pause. That moment of confusion reflects what so many people experience online today—AI is harder to spot, and it’s easier than ever to get tricked. By creating that tension, we’re helping people connect emotionally and recognize how vulnerable we all are to deception.”

Based on initial results, the verdict is out—people are ready and hungry for this kind of conversation. McAfee is already seeing an impact from these ads, with social engagement 50% above benchmark and CTR 55% above benchmark.

The second pillar of the campaign, Scam Stories, is a social series built around the voices of real scam survivors—stories from people who’ve been scammed and are speaking up to help others stay alert. From concert ticket scams to spoofed customer service texts, people are sharing their experiences using #KeepItReal and #MyScamStory, and helping others stay alert in the process. Among the first to participate are actor Chris Carmack and his wife, performer Erin Slaver, who share how even they were misled.

To extend its impact, McAfee has partnered with FightCybercrime, a nonprofit that helps people recognize, report and recover from scams. As part of the partnership, McAfee is donating $50,000 worth of online protection to individuals in FightCybercrime programs, as well as to the staff and volunteers who support them. The partnership will also include new efforts to expand online safety education.

To help drive greater awareness of the value of Scam Detector, McAfee has also partnered with several popular influencers to educate their audiences about the rise in scams and how to stay safe. Look out for comedic and informative content from recognizable names such as Alexandra Madison (@alexandramadisonn), Theo Shakes (@theo_shakes) and Kristen Knutson (@callmekristenmarie).

From surreal visuals to real-life voices, every part of the campaign was designed to blend technology and empathy, showing how creative marketing can spark conversation, shift perception and drive action. ”Keep It Real” brings McAfee’s brand purpose to life in a way that feels real, human and impossible to ignore.

Visit Scam Stories to view the campaign, submit a story or learn more about McAfee’s Scam Detector.

We’re thrilled to share that VSA took home a 2025 ANA REGGIE Award for our work with FactSet on the “Not Just the Facts” campaign. The REGGIEs—one of the most respected honors in brand activation—celebrate bold, creative campaigns that drive real business results.

“Not Just the Facts” flipped the B2B script by injecting some much-needed personality into financial services marketing. With help from our production partner Thinking Machine, we created a campaign that humorously called out the overload of data without context—making the case for FactSet’s unique ability to deliver insights that actually matter. The result was a 280% increase in brand awareness, a 438% increase in marketing qualified leads and a 76% increase in consideration.

This win is a testament to what happens when brave clients and creative teams push the boundaries of what B2B can be. Here’s to making smart ideas stand out—and to saying no to boring B2B advertising.

Very happy to share that VSA and BNY received a 2025 FCS Portfolio Award in the Business-to-Business category for the BNY rebrand. The FCS Portfolio Awards honors the best in financial marketing and communications.

BNY’s new look—including a reimagined logo—allows BNY to be more visible, bold and scalable, reflecting the dynamic nature of BNY itself. By showing up more boldly, BNY is poised to build business and strengthen its market presence.

Congratulations to BNY and the team on this well-deserved award.

Companies don’t always use data to power their brand positioning shifts. Often, it’s a subjective exercise that reflects what internal stakeholders are experiencing when they interact with customers.

That subjectivity can be dangerous for brand positioning work because it can root your brand in promises and messaging that won’t last over the long haul and may not reflect the needs of high-value growth targets.

When clients come to VSA for brand positioning work, we usually suggest their brand positioning journey start with Promise to Performance®, our proprietary quantitative research methodology.

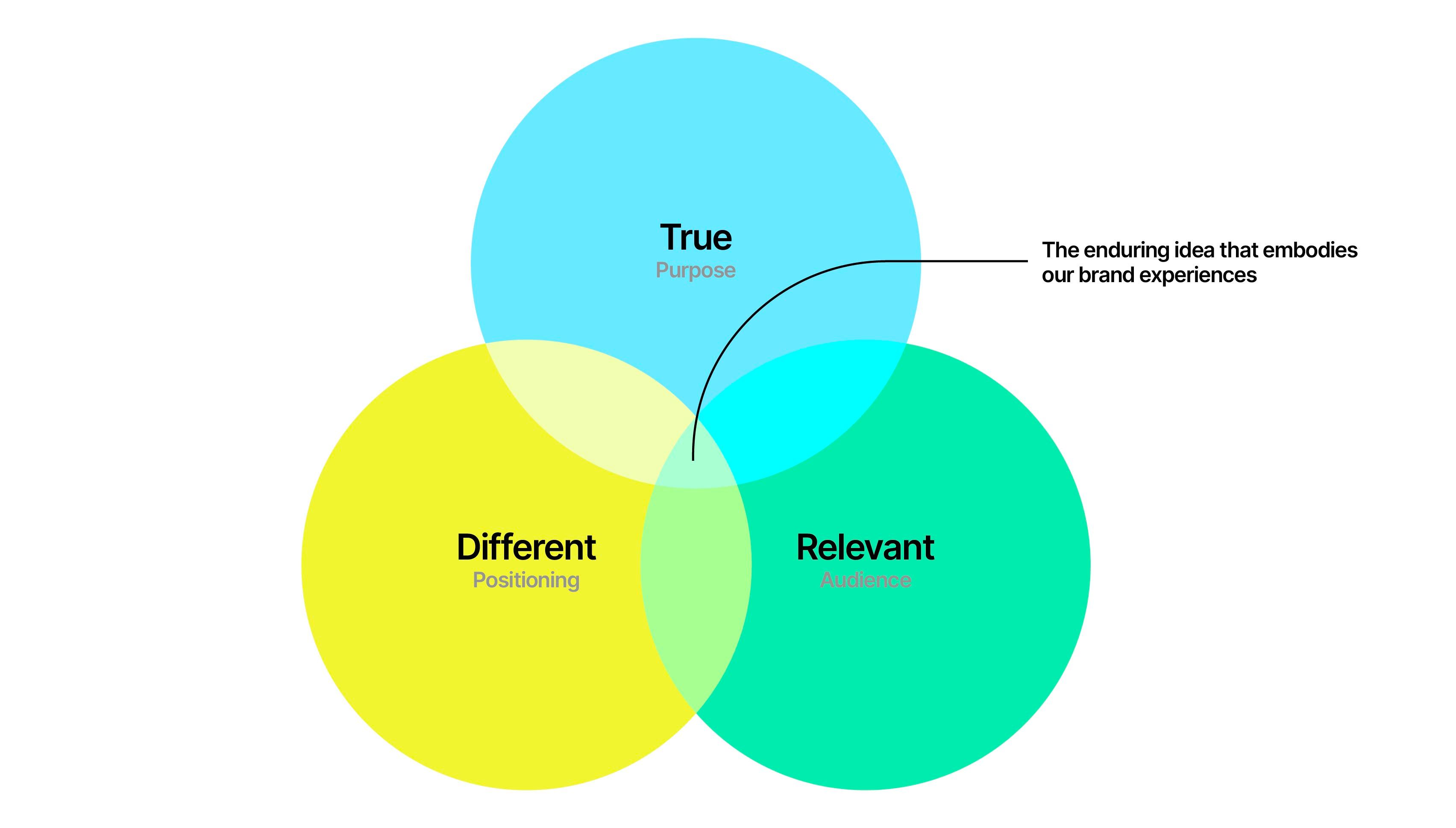

Promise to Performance (P2P) was specifically designed to identify the key ingredients of a brand positioning that is true to your business, relevant to your customers and different from what your competitors are saying. In other words, it’s everything you need, and nothing that you don’t.

P2P provides the answers to three key questions that will help you prioritize the brand promises you should focus on in your brand positioning:

In this piece, let’s focus on promise alignment to high-value audiences—why we approach it the way we do and why it matters for brand growth. We’ll cover the other two areas in future pieces.

Our approach starts with prioritizing across a long list of potential needs—about 20 unique statements, on average—to find out which are most important to each respondent in the survey. The need statements are custom written for each study to capture a range of functional and emotional needs that represent different potential priorities within your particular audience.

We then use need segmentation to define the audience cluster groups. With any segmentation exercise, there are typically foundational needs that all segments identify as important for the category. These needs are important to be competitive in the category—so it’s important to have them covered—but they are not usually differentiating.

Here’s an example: We worked with a company that offers a technology solution for small businesses. First, we surveyed their total audience, and then we performed a need cluster analysis to reveal audience segments with different priorities representing unique mindsets. In this case, all SMB segments have similar reliability and service need priorities.

One of the big benefits of doing need-based segmentation is that it can uncover the hidden gems. These are the needs that don’t immediately rise to the top in overall audience ranking of importance, but they can actually carry outsized weight for certain audiences.

For a differentiated position, we want to isolate those needs that are uniquely important to different customer segments, and then act on them.

On average we find about 4.0 segments with each study, and each segment has an average of about 3.6 needs that shape that segment—meaning, they are both important to the segment and more important for that segment compared to the audience as a whole. Often, segment-defining needs are lower ranking overall, but they over-index in importance for a particular segment. In fact, when we looked back across our P2P studies, we found that 82% of segments have at least one middle-of-the-pack need. And 45% had at least two.

Take our SMB technology provider’s audiences. You can see that some of their needs are foundational to all audiences, and some are unique to just that segment. All segments believe that reliability and great customer service are important, but within each segment there are more nuanced needs that define that particular audience.

Based on these defining needs for each segment, we can now align product capabilities, brand strengths and other reasons to believe to inform both our positioning and our messaging to the opportunity segments.

And in fact, you shouldn’t try to be. As brand marketers face tighter budgets and scrutiny over returns, you need to focus your energy where it will have the most impact. Segmenting your audience based on needs allows you to see which ones have the highest potential for growth and which ones you should deprioritize because they don’t align with the category white space and what your company can deliver.

The risk of overlooking some of the middle-of-the-pack needs becomes particularly impactful when those needs are priorities for your high-value segments. That means more likely than not, there’s something important to your high-value target that’s lurking below the surface.

Back to our technology provider example: Of the four segments, we found that two of the groups (Control Seekers and Tech Skeptics) provided no opportunity for growth at all because of their complacent mindsets toward technology.

And then we found that one additional segment (Customer Advocates) was important but wouldn’t provide the kind of growth the company was looking for.

The fourth segment (Edge Seekers) was where the real opportunity was, and where the company could focus its positioning to accelerate growth. This is a group that (1) has one-third of the market size at 36% and (2) is actively seeking a technology that can grow its business. Both the segment’s size and its mindset make it ripe for growth—and a prime audience to focus on for positioning.

This approach yields more precise, differentiated positioning that will stand out from a sea of vague brand generalities, as well as ensure that the brand is focused on the places where it stands to gain the most. You don’t need to ignore your lower-growth audiences, but you can write positioning that primarily focuses on the accelerator groups while still appealing to the lower-priority audiences.

One of the best parts of P2P is how actionable it is.

After we identify our segments, we then build profiles of these different audience members that includes their needs and how to talk to them. These profiles easily onboard your marketing and sales teams to craft messaging that speaks directly to the things these prioritized audiences care about most. Using these audience profiles, you can also relate the need-based segments to other “addressable” audience profiles that your teams are using, which can serve as a great complement to demographic segmentations.

If you’d like to work with a partner that can identify the key ingredients of a brand positioning that is unique, ownable and aligned to your audience’s core needs, we’d love to hear from you. Get in touch with us to learn more about P2P and how it can work for your business.

FactSet, a global financial digital platform and enterprise solutions provider, has partnered with Chicago-based creative agency VSA Partners to unveil a second round of spots in its “Not Just the Facts” campaign. The campaign originally launched in April this year with impressive results.

The campaign was built on a core strategic insight: While quality data is critical for financial professionals, facts in isolation provide little value. FactSet’s personalization, data connectivity, open and flexible technology, and dedicated service and support provide the context necessary for the investment community to turn facts into valuable insights—and make the most of them.

The new creative picks up where the previous left off. This time it focuses on a particularly boorish office worker, drolly played by character actor Wyndham Maxwell, who ticks off an encyclopedic list of facts and non sequiturs during business meetings and in an elevator to the bemusement of his colleagues.

The tongue-in-cheek campaign, which plays more like a perfect-pitch comedy series than a typical B2B commercial effort, is unlike anything else in the financial services industry—both in its use of humor and in its humanistic approach. Starting this week, FactSet will roll out 16 unique spots—a combination of :30s, :15s, :06s and nine “shorts”—across multiple channels including digital, streaming and CTV.

“We are thrilled with the success of our bold ‘Not Just the Facts’ campaign, which emphasizes what sets the FactSet brand apart: not just the breadth and depth of our data offering, but the intelligent solutions and advanced technology that contextualize it for global finance professionals,” said Jenifer Brooks, Chief Marketing Officer at FactSet. “We’re proud of how the campaign’s direct and relatable tone, which challenges industry norms, has resonated with audiences. As we look toward this next phase of the campaign, we will continue to bring fresh perspectives and empathetic storytelling to demonstrate the value of our offerings.”

The first round of the “Not Just the Facts” campaign earlier this year achieved outstanding results, resonating deeply and driving significant engagement. The spots achieved 193 million impressions with a 98% increase in click-through rates and a 36% rise in video view-through rates across the campaign platform.

“Humor is an incredible way to connect with audiences—and the results we saw in round one of the campaign confirm it,” said Kim Mickenberg, Associate Partner and Executive Creative Director at VSA. “In ‘Not Just the Facts,’ we’ve built a platform that lets us entertain and engage our audiences while telling a really clear, compelling story about what makes FactSet so different. We’re so proud of the work and all the collaboration that went into it.”

Los Angeles–based Docter Twins Matthew and Jason Docter directed the original campaign and this new work through their production company, Thinking Machine. The identical twin brothers grew up in the Midwest and were heavily influenced by classic comedy directors like the Coen brothers and John Hughes. Their work is known for a subtle sensibility that balances smart performance and cinematic style with a witty flair for storytelling.

“It’s tough to choose a favorite line when working with the amazing team at VSA,” said the Docter Twins. “Two of our favorites from this go-round are “‘Trees can recognize their siblings’ and ‘Some dinosaurs had really tiny arms…and could probably only bench press like 400 lbs.’

“VSA’s Kim [Mickenberg], Megan [Schulist, creative director], and Bryan [Haney, motion producer] are never short on ideas.

“And with a client like [global head of brand] Christina Sradj and others at FactSet willing to let us riff, the actors find a playful space and never let up. They were best friends by the end of the shoot, which sums up the fun we all had working together.”

FactSet (NYSE: FDS) helps the financial community to see more, think bigger, and work better. Our digital platform and enterprise solutions deliver financial data, analytics, and open technology to nearly 8,000 global clients, including over 206,000 individual users. Clients across the buy side and sell side as well as wealth managers, private equity firms, and corporations achieve more every day with our comprehensive and connected content, flexible next-generation workflow solutions, and client-centric specialized support. As a member of the S&P 500, we are committed to sustainable growth and have been recognized as one of the Best Places to Work in 2023 by Glassdoor as a Glassdoor Employees’ Choice Award winner. Learn more and follow us on X and LinkedIn.

VSA’s purpose is to design for a better human experience. As a strategy and creative agency, we blend consumer insights and data with human-centered design to activate meaningful, motivating and measurable experiences in an increasingly noisy world. With offices in Chicago and New York, VSA offers a full range of integrated capabilities—branding, advertising, data science and technology—all under one roof. VSA is also a proud member of Meet The People, an international family of unified and independent agencies. For more than 40 years, we have delivered solutions for business and creative leaders at some of the world’s most respected brands and forward-thinking organizations, including Google, Nike and IBM.

Thinking Machine is a Los Angeles–based commercial production company specializing in creative storytelling.